We need capitalism 2.0 to fix the environment

Post-growth socialism won't save us. "Natural capitalism" is the way to go.

The Contradiction Between Capitalism and Sustainability

Industrial capitalism is not sustainable. The climates are changing. The deserts are expanding. Dozens of species are on the fast lane towards extinction.

Maybe you are not bothered by these matters, because you and I live in the ivory tower of a first world nation, unscathed by the deterioration of remote environments. Fine.

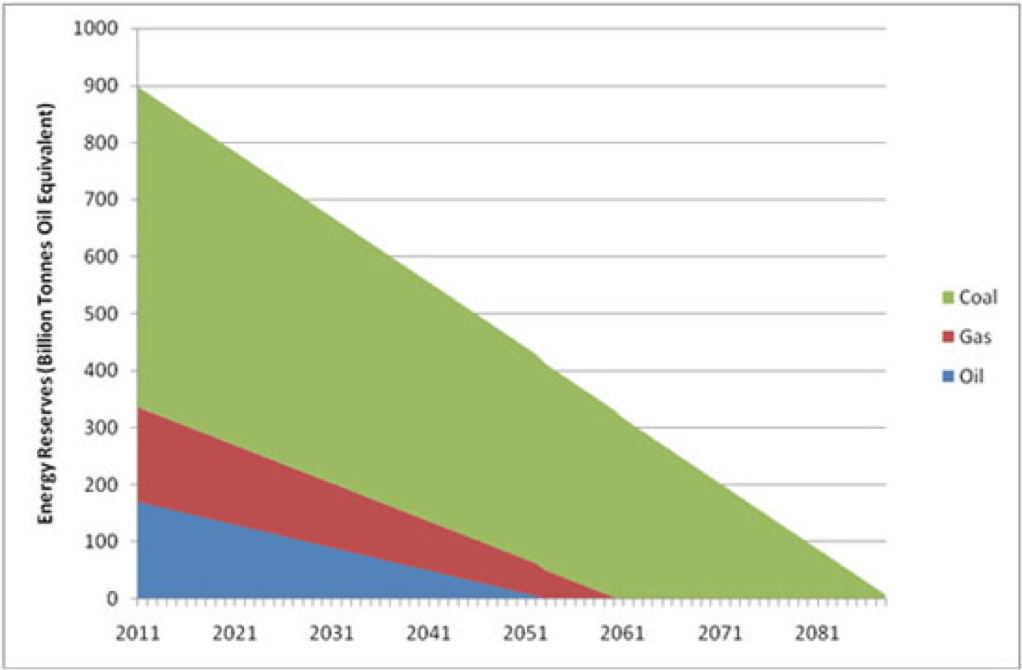

But consider this: world’s oil reserve is running out in 30 years, gas in 40 years, and coal in 70 years. Ignoring environmental problems and letting industrial capitalism “run its course” is not a permanent solution. The fact remains that industrial capitalism consumes natural resources—resources that are limited and can barely regenerate.

Industrial capitalism is not sustainable. People’s typical responses to this problem are either “we should go back to a post-growth agrarian society” or “technology will magically solve our problem.” Neither solution is sound.

A post-growth society is unrealistic. Those who’ve eaten meat do not automatically go vegan. Those who drive would not choose to walk on foot. Those who enjoyed air-conditioning would not prefer to live in heat. If you want a post-growth society, you have to convince a planet of humans to abandon their amenities and lower their life quality by their own volition. And you have to redistribute resources globally in a massive scale so that the abandonment of industrial technologies would not screw over the hunger-stricken and poverty-fested third world. One does not simply revert modernity. While I applaud the good will of agrarian socialists, I’m afraid that associating environmentalism with agrarian socialism may have only damaged the name brand of the movement.

Relying on techno-optimism is also a bad solution. Technology may or may not solve our problem. Betting on the development of technology is always risky because of its unpredictability. Humans have a track record of overestimating our techno-capability to engineer natural environments. The Biosphere 2 project poured over 200 million dollars into building an enclosed ecosystem to sustain 8 people for 2 years. It failed. Engineering the environment is costly. Even if humans developed the technology to plant trees at a massive scale, it would still cost an astronomical price to reverse the damage we have done. And who would pay for the cost?

The issue of environment reveals the limited creativity of political tribalism. The left tribe sees a problem, and throws socialism at it. The right tribe sees a problem, and throws techno-capitalism at it.

Interestingly, a third camp exists beyond the contest of tribalism. They call it natural capitalism. And I think it deserves more consideration.

Natural Capitalism

Co-created by Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins and Hunter Lovins (yes they’re married), natural capitalism tries to modify capitalism to resolve the structural contradiction between sustainability and capitalism.

Their central thesis is that the environment and its resources are an undervalued source of natural capital. The environment is a natural capital because it provides economic value—it produces oxygen, drinkable water, cultivatable soil, and burnable fuels. These resources and services are extremely costly to produce artificially. The fiasco of Biosphere 2 demonstrates this.

Market determines the price of a resource or service by its supply (availability) and demand. The market puts a price on everything our economy produces. But it puts no price on the environment nor the services it renders us.

Let’s say:

You installed a machine in your back yard. It can enrich the soil; it can beautify the scenery; it can purify the air; it takes no maintenance work; and it uses no electricity. Now, someone barged into your back yard and destroyed this machine. And fixing it takes a decade. How much would you charge your intruder? $10? $50?

The machine was a tree, of course. And as a society, we priced it at $0. Loggers can chop down as many trees in public forests as they would like, without paying a single dime. If we valued a tree in the same way we value a machine that provides similar services as a tree, we would be charging those logging companies an astronomical fee.

Loggers should be fined, because they deprive other people of the trees’ services for at least a decade, until the tree regrows. Desertifying a piece of land should be fined, because it deprives everyone of the services of the land, and it costs billions of dollars to reverse it.

If we price natural capitals in the same way as we price other forms of capitals, most of our environmental problems will go away, and sustainability will be able to co-exist with capitalistic growth.

Why Capitalism Under-price Natural Capitals

That obviously has not happened. Our market system refuses to consider the price of a tree, a piece of land, or the entirety of the environment. And there are several reasons why this is the case.

1. Environment cannot be easily monetized

A natural capital, like all capitals, should generate profit or value for its possessor. But that is not the case. Many valuable services provided by natural capitals cannot be monetized. For example, I cannot grow trees and profit from those trees because I cannot monetize the oxygen they produce nor the carbon they sequester. While a tree produces a lot of values to all humans, it does not bring me any profit or give me any exclusive value—possessing a tree gains me nothing.

Similarly, I could work hard to purify the air. But I will reap no profit from it, because I cannot monetize air. While I do get purer air to breathe from, so does everyone else. Hence, I have no motive to sacrifice my labor to purify the air. I could plant a whole forest in the America Midwest. But since no one lives there, I cannot monetize the scenery. I could save thousands of birds soaked in oil by an oil spill. But why would I do that if I cannot charge you for the beautiful bird songs you hear?

The environment provides a lot of useful services for us. But most of these services cannot be monetized because they serve everyone instead of an exclusive client who could be charged for the service.

Some of these services are also indirect: wolves provide no direct service to humans, but they play a critical role in Yellow Stone’s ecosystem. If you remove them, the whole ecosystem collapses. Capitalist market is bad at crediting indirect services and contributions. The inventor of a new drug is its patent owner. As for all the researchers whose works paved way to the creation of this drug? They don’t matter. Their indirect contribution is priced at $0—like the contribution of wolves to the Yellow Stone ecosystem.

The reason capitalism only cares about direct contribution is because the market is all about bargaining power. The immediate inventor of the new drug has bargaining power—he could withhold the drug from the manufacturer and the public if he wanted to. He owns the new drug because he controls the drug’s distribution. The indirect contributors own nothing. They control nothing and have no bargaining power.

So, unfortunately, some “natural capitals” will never be considered as “real capitals” by the market. Because there is nothing to gain from owning them.

2. Sustainability is not part of the Equation of Self-Interest

Let’s say I am running a lumber company in New England. It might be economically valuable for me to keep my woods in good shape, so the woods will continue to provide lumber for my company for centuries to come.

But screw it. I’m a selfish person, and I want as much money as possible in my lifetime. I don’t care how my company does when I’m 70 year old. So, I focus on short-term profit, and continue chopping down trees as quickly as I can.

The profit from investing in a natural capital trickles down very slowly. Stock investments generate a 10% return within a single year, or you get dividends. But if you want to invest in the health of a forest, you have to wait decades for the trees to grow before you could sell the forest at a higher price. Life is short. And few people have the patience to make decade-long investments.

Natural capitals are not only un-investable. They are also in large immediate supply. The market focuses on short-term interests. So, it sets prices natural capitals based on their short-term supply and demand. Yes, oil will run out in 30 years. But the market does not care. It sets the prices of oil based on the barrels of oil available at the present moment, which depends on the amount of oil excavated each day, instead of the total amount of oil in reserve.

The end result is unsustainable development: the lumber companies chop down as many tree as they can, the industrial factories pump out as much pollution as they want, and the oil tycoons continue to excavate oil. As selfish humans, we are eager to convert the world’s natural capitals into real money. No one wants to convert money into natural capitals because the investment takes too long to break even. So, deterioration of the environment and depreciation of natural capitals continue. The current generation continues to profit off of future ones.

3. Natural Capital is difficult to price

Selling a piece of land is different from selling used cars. Car dealers can take snip of the base model and mileage of your car, and propose a price. The pricing of natural capital is harder to determine: If I’m selling a piece of forest, how much value does a single tree add? What about a babbling stream? The services provided by a piece of natural capital is difficult to quantify. And the lack of a stable market price makes natural capitals a risky asset to invest in.

The third problem is the easiest to resolve—we just need to make better statistical assessment of a land’s value using advanced technologies (such as a drone flying over a forest to count its trees and estimate its carbon sequestration). The solutions to the other two issues are less obvious.

The environment will still be treated as worthless capitals because investors cannot profit off of it, not in the short term at least.

Reconsidering Land Ownership

The concept of ownership is engraved into the souls of modern capitalist nations. It haunts our cultures. And permeates our lives since childhood. People quibble about “who owns what” but rarely considers the morality of ownership itself.

For me to own X means I have exclusive control of X. I can ditch it. I can destroy it. Anything I do to it is morally legitimate. Ownership means absolute domination and monopoly over the property that is owned. There are two potential moral questions about ownership: transaction and the acquisition of property.

Transaction is a mutually consensual act in which two parties exchange their owned properties. Transaction is morally sensible. If I have total monopoly over my property, then, by definition I should be free to give it up in exchange for whatever I please.

What I find “questionable” is the concept of “total monopoly” and how it is acquired in the first place. Most of us acquired our properties through transactions. I bought my desk from Home Depot. Where did Home Depot get their desk from? They assembled it from pieces of lumbers. Let’s say they bought the lumbers from my lumber company. And my lumber company got its wood from chopping down trees. The lumber at the end of the day, is taken from nature. I acquired my lumber by taking from the natural capital of the whole world. Taking from the world’s natural capitals is not a transaction. There’s no mutually consenting party who consented to my taking. I just took it, like a barbaric little child who takes toys lying on the floor for himself. By the capitalist logic, there’s no free meal under heaven, so my taking is not different from “robbery”.

I might defend myself, and say “I own the piece of land, so I also own the trees that grow on it.” That’s right. But where did I get my land from? I bought it from someone. And that someone either took it from nature or bought it from someone else. Ownership was invented by humans. Before then, no one in the world held an absolute monopoly over anything. Then, the first properties emerged. And those first properties were, no doubt, taken from nature. All properties flowed from there.

Ownership—the concept of complete monopoly over something—is not as natural or morally justified as our culture believes. Ownership is always partial, and never absolute. I have partial claim to my desk, because Home Depot sold it to me. And Home Depot has partial claim to the desk because it assembled it from lumbers—it contributed to its creation. But the source material is still taken from nature, and we have no claim over things that we took.

So who owns the world’s natural capitals? Earth cannot own the natural capitals because it’s just a piece of rock. The environment is an unconscious object. So it cannot own anything. It cannot be robbed or violated. It has no moral standing. For the Theists, the answer is simple: God. God owns all natural capitals, for God made them.

For the Atheists: no one owns the natural capitals. The natural capitals were made before sentient beings. No conscious being could be credited for their creation, so nobody owns them. But that is a none-answer. Because we are still left with the question, “who gets to manage and make decisions about these natural capitals, which provide so much valuable services for us?”

Essentially, you have a bunch of resources. You have a bunch of conscious creatures whose livelihood depend on those resources. And the question is “who ought to manage those resources.” The answer is obvious: all creatures who has a stake in those resources.

Every person depends on trees, a functioning ecosystem, and an undamaged atmosphere to survive. We all have a stake in the environment. And it’s only sensible that all stakeholders’ interests are considered in the management of these capitals. In capitalist terms, natural capitals should be collectively owned.

No, I Won’t Confiscate Your Houses

The collective ownership of natural capitals does not imply communism or property confiscation. If you bought a house, you still own a large part of your house. Sure the lumbers were taken from nature, and you don’t own them. But the majority of the house’s value comes from the construction, decoration, and assembly of raw materials into usable things—and you purchased that part of your house’s value, so it is rightfully yours.

If you bought a piece of land. You don’t own the land. The land is collectively owned. That does not mean I will confiscate the land from you. After all, you did pay for it. If a thief stole a piece of jewelry and sold it to you. It would be unjust for me to punish you by confiscating the jewelry. In our case, the thief is long dead, and cannot be punished. And protecting that piece of jewelry is crucial for humanity’s survival. So, instead of snatching that jewelry from you, I remind you that your ownership of the jewelry is limited. The jewelry is placed in your possession (a weaker form of ownership). But its true owner is humanity. You may use the jewel or sell it. But you have no right to damage it or destroy it. Humanity has the final say, not you.

You may use your land normally. But if you decide to chop down all the trees, poison the whole land with radioactive materials, or deplete its fertility, humanity shall have the right to veto you, or demand redress for property damage.

The Rights of Unborn Generations

When I say “humanity,” I’m not only referring to the humans who are alive today. I am also referring to the future generations. They, too, will rely on Earth’s natural capitals for survival. They, too, have a stake in its management. Their interest ought to be considered. They must be part of the collective ownership of natural capitals.

One might object. Unborn humans are not yet conscious beings. How can they own properties? Or participate in the management of natural capitals? They can’t. But neither can infants or a demented person. Yet, an infant still owns the property bequeathed to her. If someone violates the property right of an infant, a lawyer or her legal guardian would represent her interest in court. Her representative would demand redress and compensation on her behalf.

Yes. Unborn humans cannot directly participate in the management of natural capitals. But they have clear interests and volition—they want a sustainable environment to live in. And their interests can be represented by a living agent, who can manage natural capitals on their behalf.

How do We Implement This in Reality?

How do we implement the collective ownership of natural capitals?

Option 1: The Government-Driven Approach

A body of representatives—like Congress or UN—could manage natural capitals for humanity. They may levy taxes or fines against those who use or damage our natural capitals. This could include taxing logging, deforestation, and resource excavation. And fining pollution, emission, and habitat destruction.

Essentially, corporations are purchasing full ownership of natural capitals by paying taxes. They are not allowed to chop trees down until they have purchased full ownership of those trees by paying logging taxes. They are not permitted to extract precious minerals until they had purchased that privilege through mineral excavation taxes.

Fines serve as compensations for property damage. If a company pollutes the water and disrupts the services it renders us, the company should be fined for property damage. If a corporation emits CO2, it should be fined for disrupting the atmosphere, which is also an invaluable natural capital.

The fines and taxes the government collects ought to be reinvested into the environment. It could fund projects that grow trees, restore ecosystems, or purify rivers. If the government sets the taxes and fines right. If they set the prices of natural capitals right. Then, the amount of money the government gets from “selling” natural capitals should equal the amount of money the government spends to rehabilitate or “purchase” natural capitals. And the total amount of natural capital should remain constant.

The crux of the idea is: our current society is losing natural capitals because we have been “cashing it in” for other forms of capitals. We convert forests into timber desks, because the market values wood desks above forests. Our market treats natural capitals as a source of un-monetizable and limitless resource. So, it converts them into monetizable products. The market thinks it’s playing a positive sum game—converting worthless trees into useful products. But it’s actually playing a negative sum game. The true economic values of a forest—the oxygen it produces, the carbon it sequesters, the soil it enriches—is significantly higher than its market price. So, converting forests into desks could actually be a net economic loss.

Government taxation bridge the gap between the true worth of natural capitals and its market price. Say, the true economic value of a piece of land is $10000. That’s the cost to replace all its services and goods. And say, the market prices it at $2000. The gap—$8000—is the value of indirect services of the land (again, the oxygen it produces, the carbon it sequesters, e.t.c.). A person can purchase limited possession of the land for $2000. But to acquire total ownership of the land—including the right to mess up its ecosystem by cutting down trees and e.t.c.—she needs to pay the full bill at $10000. That $8000 is collected through taxes by the government. And it is, by definition, the amount of money needed to replace the indirect services of that piece of land. For example, the $8000 could be used to plant trees that produce as much oxygen and sequester as much carbon as the original land.

The same amount of value is taken from natural capitals as is given back. So, there is no net loss in natural capitals under such a system.

But centralized ownership of natural capitals might raise eyebrows among libertarians. (And I do consider myself a social libertarian). So, I have included a decentralized alternative below.

Option 2: Decentralized Approach

Instead of entrusting our collectively owned natural capitals to an elected Congress, we can take matters into our hands. Essentially, we can manage humanity’s collective properties in the same way we manage an infant’s property: through custodial management.

The court must recognize our collective ownership of natural capitals. If a lumber corporation destroys our forest for profit, then every citizen should have the legal standing to sue the lumber corporation for damaging humanity’s collective property and depriving humanity of the forest’s services (again, the oxygen it produces, the carbon it sequesters, the soil it enriches, e.t.c.).

In essence, humanity’s interest—including that of future generations—is represented in court by a private individual or environmental organization. These entities represent the collective interest of the current generation. And they are custodians of the unborn generations, who are not yet conscious but nevertheless possess interests and rights. They file lawsuits against corporations who violate humanity’s collective property rights. They collect recompense on behalf of the existing and unborn humans.

The recompense they collect is deposited into a “custodial account”—similar to how a child’s money is managed. Custodians act as “portfolio managers” for the unborn generations. They may take money out of the “custodial account” to reinvest in natural capitals—planting trees and rehabilitating coral reefs. They cannot misuse their clients’ funds, or scam their unborn clients. If they do that, another citizen or organization would sue them on behalf of the unborn clients.

By allowing humanity and particularly unborn humans to be represented in court, we give them agency. Through their “custodians”, “agents”, or “portfolio managers”, they can collect recompense for property damage, invest in natural capitals, and they can sue in court for redress if our corporations wrong them.

The fundamental problem with unsustainable development is that we are sacrificing long term interests for short term profits. We are enriching ourselves at the expense of future generations. Hence, giving future generations legal agency and power over their collective properties eradicates the problem at its root.

The advantage of natural capitalism, as I see it, is that it confronts the structural contradiction between capitalism and sustainability head on, and resolves it. It does so through incisive surgeries, instead of relying on an unrealistic revolution to replace capitalism with agrarian socialism.

mitigating damage to wetlands and other High Value natural capital through required offsets combines gov’t regulation with a free market approach. Recent proposals to include biodiversity and carbon offsets would expand this mechanism to most forms of destructive development.

Education is a first step: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/cesar-cordova-9b202418_terrace-road-is-a-premier-cbd-residential-activity-7146533839744450560-am3e?