Critique of America's individualistic moral outlook

Are you morally obligated to do what you believe to be right? No.

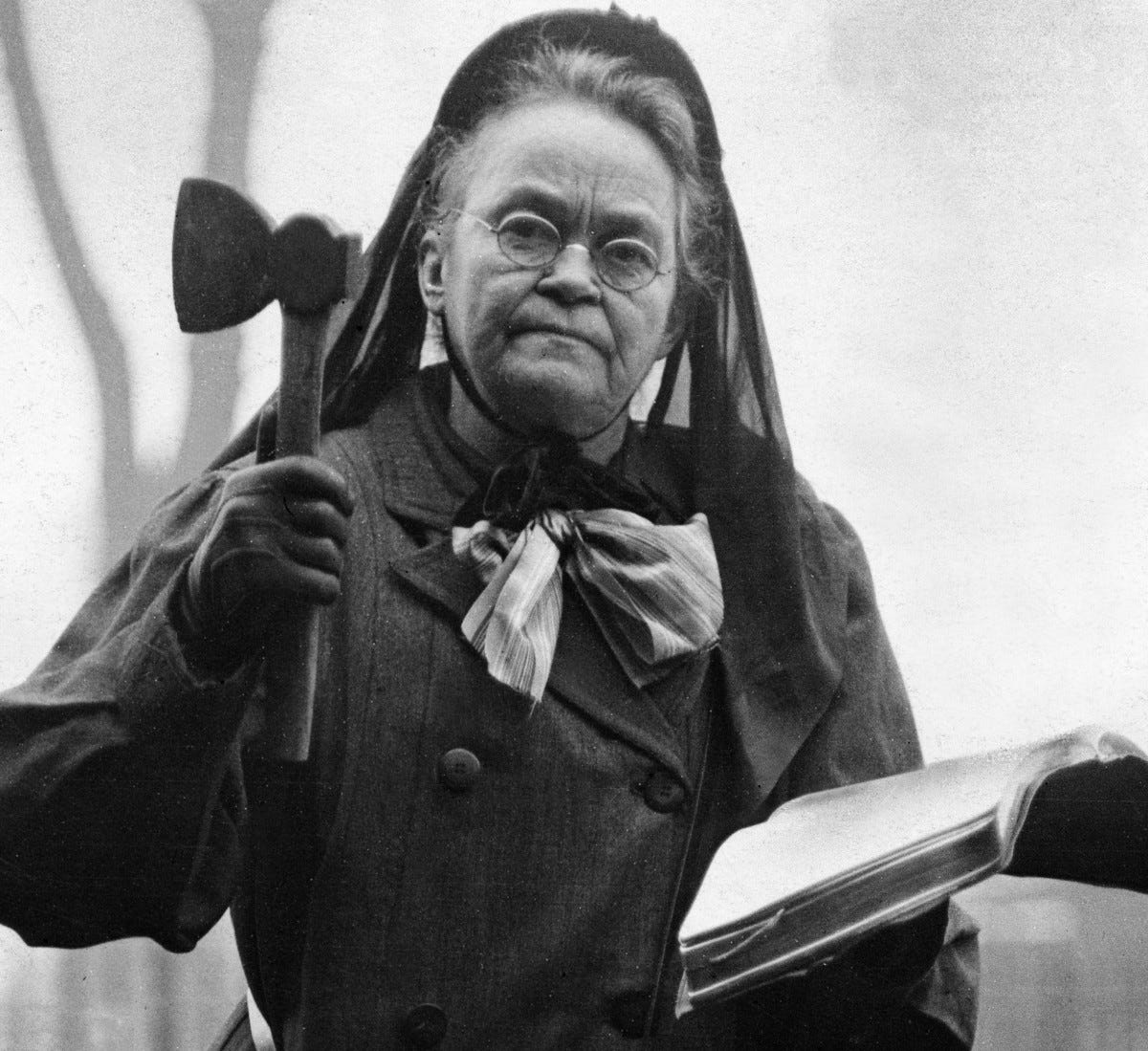

See that woman in the picture? That’s Carry Nation. Despite her positive-sounding name and genteel physique, she was the greatest anti-American supervillain in history. She was active during the 1900s, running around bars in Kansas, accompanied by hymn singing women. Of course, Nation and her hymn singing women ran into bars not to get beers—she went there to smash them up. She would march into a bar, gather the attention of the drunken men, and stand in the center, and sing. Then, she would pray to God in front of the crowd of confused and angered drinkers, like a priest preaching to a gathering of atheist. Finally, she raises her hammer, and down came destruction: bar fixtures, stocks, mirrors, bottles… Nothing can escape Carry’s rage. She would walk behind the bar stand, pull out the cash register, and dump it on the ground. Carry Nation was a menace to the hard-working Americans, who were busily gulping down their 5th bottles of beer. She was a precursor of feminism, a woman enraged by men’s drinking addictions and the nation’s implicit endorsement of alcoholic excesses. Carry Nation was also a devout follower of Christ. She described her decision of smashing up bars as a command she received from God, who said to Carry Nation, according to herself, “Go to Kiowa [Kansas], I will stand by you.” Nation interpreted this as a command to smash up bars in Kiowa. So, went to Kiowa she did. And smashed up a hell lot of bars she did. She was jailed 30 times for smashing up bars. And most notably, she was partly responsible for arousing the temperance movement—eventually giving birth to Prohibition.

It seems, nowadays, we have less of the Carry Nation type brave and good-moral vigilantes who looks upon unjust laws with spurn. Luckily, we still have Batman, and his nth reboot that is yet to come.

Individual moral intuition is considered, at least within Western culture, to be superior to laws. Those who follow their internal moral compass steadfastly, and occasionally trample the laws—like Carry Nation—are looked upon with awe. Don’t believe me? Let’s put yourself in such a situation where the law disagrees with your moral judgment. Let’s say you are in a dire situation that could very well happen in near future:

In the year of 2025, you are a doctor working in…, Kansas, where abortion is banned. A pregnant woman pleads with you to abort her child, because she never wanted it. Do you violate the law, and secretly give the woman abortion? Or, do you abide by the law, and pretend this never happened. Let’s say, you are very good at hiding secrets. So, if you secretly aborts the woman’s child, the probability of someone finding out about that matter, is very low.

The typical reader of this blog, I’m guessing, supports abortion access, so a plurality of us would choose to provide abortion access to that woman. We are inclined to violate the law, to do the thing that seems morally just to us. This concept of our moral judgments superseding the law, is very much baked in to the western mode of thinking. One reason this is the case is the fact that the laws are terrible! There are tremendous historical injustice imbued in existing laws, and it would be silly to follow along, simply for the reason that it is THE LAW. Laws can be racist, xenophobic, sexist, and etc. For those laws, it would only be right that we don’t follow them, and follow our own moral judgments instead. These laws are bad, and a plurality of people agree with us, and would like to change them; so we are well justified to regard them as nothing beyond petty historical documents.

But there are also laws / rules / orders that we don’t agree with, but the majority of people do agree with. Let’s say:

You are the president of Corruptopia, a highly corrupt, democratic republic. But you are a very righteous person. This year, the elected Congress allotted you an annual budget of $50. The congress wants you to spend $49 on fighting crimes in the country, and $1 on fighting deforestation. But you are the president, so you are the one who ultimately decides how to spend that money. Since the system is so corrupt, you can, in theory, spend the budget however you want, without risking ever getting discovered and losing your election because of it. You reason with yourself, “crimes are really bad because they kill hundreds of people each year. But deforestation is much worse. It is actively hurting everyone, and an unsustainable environment could kill all of us eventually. So, I think I’m morally obliged to spend more money on fighting deforestation, than on fighting crimes.” You bring together a team of scientist, and run a lot of environmental assessments. Their conclusion matches yours: in the long time-span of the next two centuries, fighting deforestation has much higher moral values than fighting crimes. You decide the best budget distribution is to spend $49 on reforestation, and $1 on fighting crimes. But the problem is, the majority of the people in the country disagrees with you. They agree with the Congress, because they have been living in a hell of crime for too long, and they are tired of it. So, do you follow the rules and abide by the will of your constituent? Or, will you choose to lie, and secretly spend your budget fighting deforestation, to protect the century-long greater good of your nation?

For the sake of practicality, let’s assume that the voters in Corruptopia are not stupid or short-sighted. Everyone of them is an equally rational agent—each person has the same capacity to engage in moral reasoning. If that is the case, I’m still guessing, again, that the average reader of this blog will choose to lie to their constituents—abiding by their own moral judgment, while ignoring/trivializing the moral judgment of the majority of the people.

Such an individualistic approach to morality is very much imbued in western cultures. Its roots…can be traced back to Immanuel Kant.

Individualistic Morality

The year was 1754, and Immanuel Kant, an enterprising philosopher and former private tutor, received a teaching position at the University of Königsberg in East Prussia. Those were the bustling days of enlightenment. Science was invented, with the pioneering works of Issac Newton. Philosophy thrived in the fumes of David Hume. Kant, with a stabler financial position, published a series of essays, outlining the Kantian philosophy that dominated modern philosophical thoughts for a long time to come. We are, in this post, most interested in his ideas about morality.

Kant outlined an individualistic approach to morality: that each person is born with autonomy and a capacity to reason. And in Kantian philosophy, reason is God:

“All our knowledge begins with the senses, proceeds then to the understanding, and ends with reason. There is nothing higher than reason.” —Immanuel Kant

It is, therefore, no surprise that Kant believes morality is born from reasoning. To be moral individuals, thus, requires us to constantly engage in meticulous moral reasoning about every decision we make. Can lying be allowed in Kantian morality? Well, let’s reason about it, alright?

Imagine a world where everyone makes lying promises whenever that gets them something they want. Since everyone knows that other people could be lying to them when they promise something, nobody will trust the promise made by another person. If nobody trusts the promise made by another person, then you cannot make lying promises anymore. Because the whole point of about lying promises is to deceive other people into believing in your promise, so that you can take advantage of them. But since no one in this imagined universe will believe in your promises, there’s no point in trying to deceive them. A universe—where lying is a permitted moral law—leads to logical self-contradiction. In Kantian morality, therefore, lying is not permitted.

Since, to Kant, individual reasoning is the most reliable way to arrive at moral truth, whenever there is a conflict between your individual moral reasoning, and the common law provisioned by a state, Kant would urge you to follow your moral conscience, even if that means trampling over the law. There is no God of moral authority, who provisions the truths of morality to the common person. The only God is reason. Each person’s individual moral reasoning, is the only source of moral truth. We should, therefore, not put our faith in the moral knowledge of some authority figure, but reason for ourselves what is right to do.

Robert Wolff, a famous philosopher, in his seminal book In Defense of Anarchism, would take the idea further. Wolff argues that, not only should we value our moral reasoning above the laws prescribed to us by the state or some other authority figure, we are obligated to do this. Every person has the responsibility to act morally and make moral decisions. The only way to determine if a decision is moral, according to Kant and Wolff, is to engage in moral reasoning about that decision, and act in accordance with our moral reasoning. So, that means, to be a moral person, we must always engage in careful moral deliberations about decisions we make, and act out of our own moral reasoning. We should never place faith in any sort of moral authority, be it a law provisioned by the state, or a priest preaching from the alter.

Let’s say, one day your landlord comes bumbling into your apartment, to collect your due rents. As a nice tenant and a law abiding citizen, you might happily hand over your rent to the landlord. It’s a natural reflex, like the jerking of a frog’s leg when you shock it with electricity. Your justification is instinctive. You don’t need to think about it: paying rent is a law, so it is only right if I follow it. But then Kant and Wolff would jump out from behind the door. Hold on a second, they say. How do you know this rent collecting law is moral and just? Have you sat in a cave for 30 days and meditated about the morality of tenant laws? If not, how do you know you are acting morally, when you hand over your sack of money to the landlord? Wolff will go further, and attack you for giving up your rent: How dare you act without first thinking? Is it not your responsibility to act morally? Is not individual reasoning the only way to arrive at moral truth? If that is so, wouldn’t you agree, that you have the obligation to reason about every single thing before acting, so that you can ensure your actions are always moral?

To Wolff, the blind acceptance of law is immoral! We must always abide by our individual reasoning, instead of the law. We may follow the law, when our own reasoning aligns with the law. But the moment that our moral reasoning and judgments diverge from the law, we must, according to Wolff, abide by our moral reasoning instead. Hence is why Wolff is known to be an anarchist.

While the average American probably have not heard of Wolff or Kant’s arguments, the underpinning of these arguments are already baked in to our collective way of cultural intuitions. When you got your traffic ticket last month, your first thought wasn’t, Oh I feel so guilty for speeding to 200 miles on Main Street. Let’s be honest, the moment you got your ticket, you were probably cursing the police department, Morons! I was hurrying to some very important business don’t you see? Your first instincts are to trust your own moral reasoning, rather than the moral law of the country.

Batman and Carry Nation would agree with you, in their passionate crusade to right the wrongs of society. Moral intuitions are much more important than laws! Batman, Carry Nation, and the angry you who just got fined a ticket—you are not overwhelmed by emotions; you are not dangerous vigilante; you are not cartoonic self-righteous Jesus dressed in a bat suit—you are all sophisticated Kantian philosophers! Congratulations! Tell that to your old man, the next time he complains about you failing to follow societal orders.

This blog post is not exactly intended to be a Ponzi scheme to bring about an anarchist revolution, or a revival in Kantian fanfare. I just want to bring to your attention, that there’s an individualistic moral philosophy framework underlying our natural contemptuous attitudes towards laws in America. And, in fact, I don’t think it is a great idea that lawlessness or vigilantism is encouraged. There’re certain benefits of a society where the common law is respected—these societies are more secure and peaceful.

I lived and went to school in China, the polar opposite of America. The public schools in China are the fairylands of communist propaganda. I remember there was a mandatory class I took, called “Morality and Law,” which was basically a 45-minute period each day dedicated to baking “respect for law, and submission to law” into the mind of every 9-year-old in the country. The trust in laws is a blind faith in China. “Love thy comrades…, thou shalt not steal” preaches the teacher from the podium, and the students mutter along. There’re obvious defects to such a society…but there are also benefits most westerners would not condescend to consider. China is an extremely secure country…, and police are often no where to be seen on streets. Almost every citizen is law abiding, not out of fear of some secret police force,—law breaking is simply a concept that seems well beyond the mind of the average, well-indoctrinated Chinese citizen.

It makes sense. When people are taught to respect the law, they are much more likely to follow it. Americans, on the other hand, look upon law abidance with spurn. Americans look at the issue with a natural bias—trusting one’s individual moral judgment over the authority of the common law. It may not surprise you, given Americans’ distrust of laws, that the US has a…relatively high crime rate.

Communal Morality

But what exactly is wrong about Wolff’s philosophical arguments? Of course, I’m not going to be one of THOSE people, who randomly criticizes a particular philosophy or way of thinking without giving decent reasons. I think the mistake of Wolff starts from his assumption, that moral truth is best arrived at through individual reasoning. And it is best illustrated with an example.

Consider Jonny, an incurable sociopath who hates humanity. Jonny, like every other human, has a good capacity to reason, and the autonomy to make choices for himself. However, Jonny’s moral outlook is very different from other folks living in this world. Most people believe that suffering is bad. There’s no reasoning to argue for why suffering is bad; it is simply a moral premise that everyone accepts—everyone except Jonny. Jonny is a sadist and a masochist. His brain is just wired differently than the normal humans. He thinks suffering is very good. So, one day, Jonny tortures a young man named Harry. Jonny is arrested, and brought in front of the court. His defense is: I don’t believe suffering is bad. So, after engaging in an hour of deep moral reasoning, I decided that torturing Harry is not a morally objectionable thing to do. That is why I tortured him. I followed my moral reasoning, and abode by my moral conscience thoroughly. Therefore, I acted morally, and should be acquitted.

Thank goodness, the jury haven’t read Wolff’s In Defense of Anarchism, so they indicted Jonny for the assault.

If we abide by Wolff’s philosophy strictly, everything Jonny did was morally correct—he followed his own moral conscience instead of caving in to the common law. But that’s ridiculous! How can it be morally right for Jonny to assault and torture another human being?

I hope, you will agree with me at this point, that there is something fishy about Wolff’s argument. What is wrong, I think, is Wolff assigns the moral authority of judging “what is right” to Jonny, the actor of the action, instead of to “Harry” recipient of the action.

Sure, torturing people may seem right, and justifiable by moral reasoning, to Jonny. But it doesn’t matter what he thinks of his action! His actions are acted upon Harry. So, Harry is the person who is bearing all the consequences of Jonny’s action. As the recipient of Jonny’s action, Harry should be the person who gets to decide whether the action is moral or immoral. Harry, in this case, after meditating in a cave for a number of hours, will hopefully decide that Jonny’s assault on him is immoral. Even though Jonny, himself, may enjoy torture and being tortured—even though Jonny would not agree with Harry—it doesn’t matter what Jonny believes in or thinks. Being the recipient of all the consequences of this action, Harry has all the moral authority to decide if it is moral, or immoral.

To understand the morality of an action, we must not just look at it from the perspective of the actor, but also consider the perspective of the recipient. In many cases, such as when the consequences of the action falls mostly upon the recipient, then the recipient’s moral reasoning are far more important than the moral judgment of the actor. The responsibility of Jonny is not to act in accordance with his own moral judgment, as Wolff asserts. His responsibility is to act in accordance with Harry’s moral judgment. Since Harry believes suffering is bad, and torturing is immoral, Jonny has the moral obligation to not subject Harry to any torture. Let’s call this form of morality communal morality, in contrast to the individualistic morality put forth by Kant and Wolff.

Far distinct from Kant and Wolff’s individualistic morality, which only requires an individual to reflect upon what he believes about his actions, communal morality requires each person to understand the perspective of others. Each person ought to act, such that she does not subject others to consequences that they don’t consider to be moral—even if she, herself, considers those consequences to be moral. To put it more plainly, each person should not subject others to consequences they don’t deserve.1

Why we should abide by the common law

I am not Mr. Law and Order, and I don’t believe in some innate authority of the LAW. But, I think there is a good moral point to make, for abiding by most of the common law in a DEMOCRACY (again, there are bad laws, created by historical injustices; they are a separate question). If you don’t live in a democracy, I encourage you to challenge laws, based on your own moral reasoning, as long as it doesn’t get you hanged…which it probably would…in most existing systems that aren’t democratic…

Laws in democracies have a special feature, which sets them apart. That is: these laws are made by the consensus of society. A plurality of people, after engaging in their own individual moral reasoning, decide to enact these moral laws—through referendums, elected representative legislators, and e.t.c…at least…theoretically. Each individual should abide by these moral laws, in their daily interactions with society. We should do this because our actions impact society. So, part of the moral arbitration of our actions depends on what society think of these actions. Does a majority of people in society think our actions are moral? Or is there a majority of people who think our actions are immoral? Laws, because they are established through democratic consensus, are statements that indicate what society at large think of our actions. Laws are society’s moral judgments of our actions. Even if we don’t agree with these judgments at times, these judgments have validity because our actions have impacts on society—so it matters what society thinks of the morality of those impacts.

If I emit tons of CO2, by burping unstop 24/7, that is going to have a negative impact on society—by increasing global temperature ever slightly. Society may judge my burping to be immoral, because it creates a negative impact on the environmental well-being of society at large. It is, therefore, completely justifiable, if society decides to fine me for burping too often. I may feel it unfair that I’m taxed by society for burping, because I have the weird religious belief that burping is good for the world. It doesn’t matter what I think of burping. It matters what society at large thinks of burping, since society is the one that is bearing the consequences of my burps—it has the moral right to decide if those consequences are good/moral or bad/immoral for itself.

So, next time you are rushing to work, flying through Main Street at 200 mph, and receive a fine. Just accept the fine. It’s not entirely up to you to decide if your speeding is excusable or not. That right lies, in part, with society. And society made its decision through traffic laws.

Oh, and did I mention…Don’t dress up like a bat and walk around killing people in the name of Justice.

Of course, Kant and Wolff are not fools who didn’t anticipate this argument. There’s a subtlety here that I did not explain. Kant and Wolff believe morality to be absolute. That means, if two people both engage in rational reasoning, they should arrive at the same moral truth, instead of divergent ones. My belief is, of course, that there is no absolute moral truth. Morality is just a set of instincts we evolved as a specie for survival and better interactions with our peers. Therefore, it is entirely plausible for two people to have different moral beliefs even if they use rigorous reasoning—because they start from different moral premises. This fundamental belief difference is, in fact, the source of my disagreements with those philosophers.