Ethics study is running around a definitional carousel

There is no such thing as a right system for morality, because the value judgment of something as “right” is itself a moral assertion that depends on the moral system we adopt.

There is no such thing as a right system for morality, because the value judgment of something as “right” is itself a moral assertion that depends on the moral system we adopt. Philosophers have spent centuries pontificating about the “true nature” of morality. Religious scholars regard morality as a fact of nature, handed down to us by God, much like the good earth we inhabit. Morality is decreed by a supremely perfect God, Descartes argued in the 17th century.

A century later, the genesis of Enlightenment dethroned religion from moral discourse. The “enlightened” rationalists worshipped Reason in place of an anthropomorphic God. Kant proposed the Categorical Imperative theory, which attempts to construct human morality from the very Laws of Logic, plus a tiny set of assumptions. Kantian ethics ushered in an era of logical ethics.

Philosophers take turns building their ethics system from a tiny set of moral axioms (or assumptions). Typical assumptions philosophers make include “every person has equal moral value” (principle of equality), “if you act by a certain principle, you must expect others to also follow the same moral principle” (universalization axiom), and “murder is immoral” (not-kill-human-ism). These axioms function as lego pieces. We can piece them together using the rules of logic to derive secondary moral laws, tertiary moral laws, and so on. And the collection of all these moral derivatives constitutes a logically coherent moral system.

Philosophers quip over the correctness of these moral systems in an attempt to reach THE “correct” moral system. One way to argue against a moral system is to show that its axioms contradict each other in some exceptional moral scenario. Although you may never encounter these scenarios in real life, you can still dream them up in thought experiments.

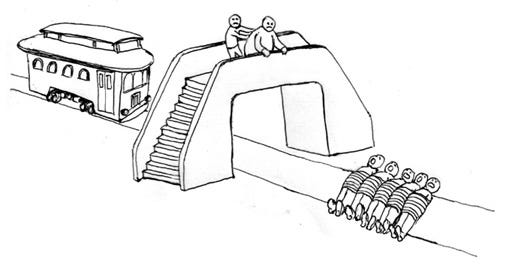

For example, in the Trolley Car thought experiment, a trolley car is hurtling down a track where 5 people lie. You can choose to leave those 5 people to crushing death beneath the wheels of the car. Or, you can push one stout man down the track to stop the trolley car from taking those 5 lives. Which pill would you swallow? Would you save 5 at the expense of 1? Or would you refrain from the nasty act of murder. If you value the 5 people’s life above the stout man’s life, then you are either a misandrist or a believer in the Principle of Equality. Since you believe each life to be equally valuable, you weigh 5 lives more than 1. A strict not-kill-human-ist, however, would choose not to murder the stout man even if it condemns 5 others to a fatal fate. To them, killing is a red line we should not cross, no matter how many extra lives it saves.

We can adopt the Equality Principle, or we could stick with the principle that “murder is immoral.” But we cannot adopt both moral axioms at the same time since they reach different logical ends in the scenario of the Trolley Car problem. Therefore, we can conclude that any moral system that adopts both principles is necessarily logically inconsistent. This makes the moral system bad or at least incomplete, because it is inconclusive for moral problems where two assumptions logically lead to different conclusions.

Philosophers can also undermine a moral system by making value appeals. It works like this: say, your moral system guides us to do X in one situation. But, according to some other very credible-sounding moral assumption], you should do Y instead. Therefore, I can make the case that your moral system is just wrong. Alternatively, we can skip the logical gymnastics and just claim that doing X in this situation is ridiculous, because it does not align with our moral intuitions. And we reach the same conclusion that any ethics system advocating for X are just boners. These are formal deductive philosophy arguments. Philosophers usually sculpt their arguments and polish their diction until they are logically infallible, and then package them into neat little essays to publish onto peer-reviewed journals. They enjoy life for a couple of months until some other philosophers jump out of the bush to publish some counter-arguments against their arguments. Then they are busy back at work defending their original thesis.

This is how ethics developed through the centuries—as a continuum of arguments and counter-arguments. People cooked up all sorts of moral systems (consequentialism, utilitarianism, Kantian ethics, Rossian deontology, virtue ethics, contractualism, e.t.c.), and made myriads of arguments for and against each. Consequentialism, deontology, and virtue ethics each vied for public attention but cannot quite take out its rivals. For every argument a deontologist hauls at a consequentialist, a consequentialist snaps back with an equally strong rebuttal. Arguments piled on top of arguments, and the discourse grew like a balloon inflating in no particular direction.

Centuries passed yet progress remains elusive. Modern ethic frameworks produced by 21st century philosophers are not universally recognized to be superior to museum antiques like Kantian ethics from the 18th century. Nobody agreed on any consensus of what the “best available moral system” is. You can as easily find some old-fashioned Aristotelian virtue ethicist running around the street these days as you can find a Peter Singer-style hardcore utilitarian. If the end-goal of ethics study is to produce THE CORRECT normative moral system, then we can hardly claim any tangible progress.

Ethics is not like science, where progress is consistent and measurable: physicists almost unanimously agree that special relativity is a better physical model than Newtonian mechanics; general relativity trumps special relativity; and quantum physics is superior to all classical models since it will likely become the ONE model to rule them all. We can compare the merits of physical models because we can make predictions using these models, and see how accurately they match up with what happens in the real world, or at least what happens in our phenomenological experiences of the real world. This is the doctrine of empiricism. It provides us with the means to evaluate a theory or model by assigning higher values to more predictive models.

Empiricism makes sense! When a physicist asks “what is the world like,” she is entreating us to provide a description of reality that matches her experience of this reality. And the way she knows whether a description is good or bad is by assessing how closely the description resembles reality. In doing so, she is using the doctrine of empiricism, which allows her to produce models of the world with increasing likeness to her actual experience of it. Therefore, she is able to provide ever better answers to the question “what is reality like.”

Ethicists, on the other hand, are running into a brick wall. They do not care as much about what morality is like (it is a set of pro-social instincts our ancestors evolved to improve their inclusive fitness). Ethicists want to know what morality ought to be like, normatively. What ought we do in the Trolley Car scenario? What ought we do when the rights of free expression disrupt communal harmony? What ought we do when the welfare of animals is pitted against the need to feed hungry humans. These kinds of “ought” questions (or normative questions as philosophers smugly call them) have tremendous practical values, but they are difficult because they are not asking us to describe something. There is no such a thing as a Law of Morality in the rulebook of the universe that we are trying to describe with our moral theories. The equations of physics do not contain a term that prescribes the ultimate moral code humans ought to follow. So we cannot answer the “ought” question by simply fashioning moral theories in the likeness of some measurable ground truth. We cannot gauge the merits of our moral systems by comparing them against some cosmic moral truth. Empiricism does not apply. We are left to muse about morality in our little brains, inventing moral theories that we cannot evaluate.

Given the way I described ethics study, it might seem quite obvious that the entire project of normative ethics is futile—a hunt for a phantom that does not exist. But most ethicists do not realize this. They continue to propound moral theories and assert the superiority of one moral system over another. The fallacy these ethicists commit is that they are not evaluating these moral systems by some stipulated rules. They are assessing moral systems based on whether or not those moral systems align with their own values. They argue for and against moral systems using moral assumptions that draw from their personal values.

For example, in the context of the Trolley Car experiment, Kant famously rejected the Equality Principle argument for sacrificing the stout man by arguing that you cannot push the stout man down the rail track because you objectify him. According to Kant, a person should never be used as a means to an end. Every person should be respected, and treated as an end in of himself, so you ought not use the stout man as a tool to block the trolley car. While Kant’s argument is neat, it is in no way a justified rebuttal of a moral system founded on the axiom of the equality principle. All Kant did is he cooked up a different piece of moral axiom (“don’t treat humans as means to an end”), and said, look your moral system produces a result that conflicts with my respect-human-axiom, so your moral system must be bad. Kant essentially rebuked utilitarianism by saying that it produces results that conflict with his own moral system. He did not actually prove utilitarianism to be inferior. He only proved that it is incompatible with his own ethics system.

Unfortunately, Kant is not alone in committing this fallacy. I claim that the entire field of ethics study is quite complicit in condoning these fake merit arguments. In fact, any argument against a moral system that draws on moral assumptions not made by that system is just a statement of the incompatibility between the system and those assumptions. And quite frequently these incompatibility arguments masquerade as merit arguments for some moral systems over others.

So centuries of ethics arguments have not really been meaningful discourse over which moral assumptions we ought to include in a normatively ideal moral system. Ethicists have just been yelling over each other about why others’ moral systems are wrong because those systems contradict with some moral axioms they personally adopt.

Please know that I am not claiming the work of ethicists to be entirely fruitless. Ethicists produced a plethora of moral systems that give us a good idea of the range of legitimate-sounding moral systems we can construct. And the incompatibility arguments ethicists laid out can also tell us which moral axioms are logically incompatible with each other. For example, we now know that ethics can be subdivided into three largely incompatible frameworks—deontology (morality depends on what a person does), consequentialism (morality depends on what consequences a person’s action produces), and virtue ethics (morality is what a virtuous person would do). The core moral assumptions behind these three moral frameworks turn out to be incompatible with each other. Ethicists have also done a great job answering the question “what human ethics is like” while they are trying to figure out “what morality ought to be like.” While the approach ethicists take—arguing for and against moral systems based on how well they align with our own values—cannot answer the ought question, it is quite effective at producing moral systems that resemble our evolved moral intuitions. By assessing moral theories based on whether or not they agree with our moral instincts or the moral axioms we personally adopt, we are essentially molding moral systems to reflect our instinctual moral values. When a large number of philosophers do this together and iron out their less-significant differences, we would arrive at a moral system that best resembles humanity’s evolved moral instincts. We would have answered the question, “what human morality is like” while making little progress on the question, “what the right moral system is like.”

The normative question remains beyond grasp. I claim that it is in fact unanswerable because the question itself is illogical. The very question “what the right moral system is like” implies the existence of a distinction between “right” moral systems and “wrong” moral systems. But judging something as “right” versus “wrong” is itself a moral judgement. And every moral judgement must be predicated on some moral system because a moral system is, by definition, a formula for making moral judgements.

We employ some moral system every time we make a moral judgement. When a utilitarian decides that killing 1 to save 5 is right, she is using the utilitarian moral system to make that judgement. When Kant says objectifying humans is wrong, he is leveraging the Kantian ethics system to hedge that claim. And when a layman argues that murder is obviously wrong, he is using the ethics system that comprises his evolved moral instincts to make that call. Similarly, when we claim that Kantian ethics is righter than utilitarianism, we are employing some third-party moral system to make that judgement. So, the meta moral question “which moral system is right” has no universal answer, because it depends on the moral system you use to decide what is right. And we do not know which is the right moral system for making this meta-assessment because it requires us to know “what the right moral system is”, which was the question we started out with. In order to find out “what the right moral system is like” we have to first know “what the right moral system is”, which we obviously don’t. So, the question “what the right moral system is like” cannot be answered. It’s a definitional carousel revolving around the word “right”.

The word “right” indeed did a lot of heavy-lifting in my argument. I made some assumptions about its definition during the mental acrobatics of the last paragraph. And we might be justifiably concerned by them. In particular, I assumed that the question “whether a moral system is right” is a moral question. But it might not be. For example, whether the answer to a math problem is right is not a moral question; whether a physics theory is right is also not a moral question. “Right” is used in many fashions.

Sometimes, “rightness” is subjective, but other times it is absolute. 1+1=2, for instance, is absolutely right; 1+1=3 is absolutely wrong. 1+1=2 is a logical statement given the mathematical definitions of the numbers “1”, “2”, the addition operator “+”, and the equality relation “=”. 1+1=3, however, is an illogical statement. Therefore, in the context of mathematics, “rightness” means “logically consistent.” A statement that is logically coherent to one person is logically coherent to every other person, because the rules of logic are universal. Logic questions have objective, universal answers. We can ask ourselves “whether a moral system is logically coherent.” That is a valid logic query with an unambiguous answer. But there are many moral systems that are logically self-consistent; which one is the “right” one? Clearly, for a moral system to be considered the “right” one, it needs to be more than logically coherent. The concept “rightness” as used for moral systems entails something more than “logical correctness.”

It also means something quite different from the concept of “factual rightness” we use in physics. When we claim a moral system is wrong, we mean something very different from when we say a physics theory is wrong. In the context of science, the distinction between right and wrong arises from empiricist evaluation. We compare the predictions of a scientific model to reality, or our phenomenological experience of it. And we designate the model as wrong if its predictions differ from reality. In the empiricist doctrine, reality—the thing that our models try to imitate—is the anchor for rightness and wrongness. Morality works differently because there is no such a thing as a moral truth ingrained in reality that we can reference against to determine if our moral system is right or wrong. There are no moral truths written into the physical laws of this universe.

We might be tempted to hope that perhaps moral truths exist in a separate spiritual or metaphysical realm that our scientific measurements can never access. But this is wishful thinking, akin to Nietzsche’s lamentation of the Death of God. Nonetheless, it can be true. But even if moral truths succeed in lurking from science within some spiritual realm, they cannot be accessed. If these moral truths were accessible through measurements of reality or our phenomenological experiences, they can be analyzed through the doctrine of empiricism and eventually described by some theory of science. So, for moral truths to elude science is for it to be inaccessible to humans. And their inaccessibility renders them useless. If we cannot access these moral truths, we cannot compare them to our moral systems to decide if our moral systems are factually right or wrong. Therefore, even if metaphysical moral truths exist, they cannot be used to answer the question “which moral system is right”.

We are lost. We have no way of knowing objectively whether a moral system is right or wrong. And we have no way of finding the “right” moral system that philosophers have adamantly sought for in the past several centuries. We ask the universe “what ought we do” and “which moral system ought we adopt” but we receive no answers, because the universe is impartial to whatever decisions we make and whichever moral system we choose. The universe does not prefer one action over the other or one moral system to another, because it is an inanimate object without preferences. We are the ones who care about these issues. It is precisely because we have such strong personal preferences for some moral systems over others that we spent centuries bickering over the merits of different moral systems.

So, instead of asking the universe which moral system we ought to adopt, perhaps we ought to ask ourselves which moral framework we would prefer. Instead of treating morality like some hidden truth to be discovered, we should approach morality as a set of practical social rules for societal organization—some more preferrable than others.

Imagine a myriad of societies governed by different moral systems. Which of these societies would you personally prefer to live in? There is no “right” answer to such a question. Some moral systems produce more desirable societies than others. For example, a society that endorses equal rights would likely be more pleasant to live in and more popular than a society with hierarchical oppression. Different people can prefer different societies. I would prefer a virtue ethicist society over an act utilitarian society because I prefer not to have my organ harvested for some “greater purpose”. Perhaps you would instead prefer a utilitarian society because you are a risk taker and only care about maximizing the expected pleasure over your lifetime. Perhaps somebody would prefer a moral system that privileges them over other people. But other people probably would not live in such a society. So societies with very unreasonable moral systems are unlikely to be feasible.

I know that “preference” is not necessarily the best framework for thinking about morality. But at least we can begin to work out “which moral systems are more preferrable.” On the other hand, we will never discover the “right” moral system that we purport to exist.

Hmm, interesting take Michael! Also, nice to meet you IRL on Saturday :)

Me personally I believe that self-consistency is the only good normative ethical framework 💪

Also, disagree that empirics makes sense? Also, check out Utilitarianism: for and against — specifically J. J. Smart's section (against), cus he just spends the whole time dunking on any moral framework vs. specifically util. (You can also read his wikipedia his arguments against kantianism & util are the same.)

Also, question: if you believe there is no point in finding the "right" moral framework, why study philosophy?